THE AMBOSELI ECOSYSTEM

Here we present a deeper look at the components that make up the intricate Amboseli ecosystem: ecological, cultural, and political.

NEW THREATS TO AMBOSELI AND MOBILIZING RESPONSES

The threats to East Africa's magnificent savannas come in many forms and Amboseli faces most of them.By far the gravest danger lies in the fragmentation of the 10,000 square kilometer ecosystem and collapse of the migratory herds of zebra, wildebeest, elephants and pastoral livestock. The seasonal migrations and movement of wildlife through habitats of the Amboseli Basin each dry season has kept the savannas productive and animals able to ride out droughts and recover in good years. The migrations and free-ranging movements of wildlife and pastoral livestock in response to local conditions and each other have allowed them to coexist in the Amboseli ecosystem for millennia: ACP over the years has documented the patterns of migration in Amboseli and explained how so much wildlife and so many livestock thrived in the same area and maintained the richness of habitats and productivity of pastures. The information is given in the report titled The Ecology and Changes of the Amboseli Ecosystem: Recommendations for Planning and Conservation (see under Amboseli Ecosystem). The report lays out the minimum conditions needed to sustain the wildlife and biodiversity of the Amboseli ecosystem and the array of threats its faces from rising population, the spread of farming, water diversion, subdivision of land, habitat loss, falling pasture productivity and poaching. The combined pressures on the ecosystem over the last three decades have seen the late season pastures shrink and decline. Severe forage shortages in the national park and surrounding Maasai ranches have grown more frequent and intense. The shrinking pastures culminated in precipitous declines in Amboseli's wildlife and Maasai herds in 2009 (See The Worst Drought: Tipping Point or Turning Point). The recovery from the drought is far slower than in previous droughts. Our ACP website reports on the slow pace of recovery as well as the likely causes and consequences in an update below. In the last two years new threats have arisen in Amboseli. The gravest threat stems from the inexplicable government plans to build a Nairobi Metropolitan township on the boundary of the park and a new highway through the migratory routes northwards from Amboseli. Why Nairobi Metropolitan Area needs Satellite Township 150 kilometers away speaks to political intent rather than rational planning. Both the proposed town and road have been floated with no reference to the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan and or public hearings in the region. Yet another threat arises from the rapid pace of subdivision of land on the eastern border of Amboseli, a rash of new lodges and land sales to outsiders speculating on rising property prices. The resurgence of ivory poaching that killed off over 100,000 of Kenya's elephants in the 1970s and 1980s also threatens the Amboseli herds. Further details can be found on the Big Life and Amboseli Elephant Trust websites. The surge in ivory demand in China since 2010 and the rise in price to an all-time high of $1,000 a kilo has sent poachers in pursuit of elephants across Africa, accounting for 25,000 dead in 2011. Tanzania is losing 10,000 elephants a year. Kenya, at close to 400 officially last year, and certainly more in unaccounted elephants, has fared better. The difference comes down to superior KWS anti-poaching and intelligence capacity and strong community conservation initiatives and scouting patrols. In Amboseli community conservation efforts have kept down poaching as they did in the 1980s. The success is in large part due to the 350 community scouts who patrol the areas outside the park. Despite the security network, poachers have infiltrated Amboseli several times in the last three years. Big money, ivory cartels, small arms, corruption and rural farmers and herders out to make do in hard times add up to a formidable threat to elephants in Amboseli. And Amboseli's elephants link up with other herds across the entire Kenya-Tanzania borderlands where one of the largest bushed savanna populations move between and beyond the world famous national parks from Serengeti-Mara to Tsavo. The following reports give a thumb-nail sketch of the threats to Amboseli ecosystem and some of the responses underway. Regular updates will be posted on the ACP website. Download the full report here. BIOMATHEMATICS WORKSHOP

Recently ACP staff helped to organize and participated in a five day biomathematics modelling workshop facilitated by the French Institute for Research and Development (IRD), the University of Nairobi School of Mathematics (UNSOM), Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), African Conservation Centre (ACC), and the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology. Anna Sakellariadis joined the participants at the public day on 4th November at the KWS and offers the following impressions: At the public day for the National Biomathematics Workshop on November 4th, the topics du jour were the training of Kenyans in biomathematical modeling and its applications to decision-making in ecology and epidemiology. Following four days of practical teaching sessions in Naro Moru River Lodge, Nanyuki, the public day reconvened participants and organizers at Kenya Wildlife Service headquarters in Nairobi. It allowed the organizers to reflect on the workshop proceedings and how to move forward. Heads of the organizing institutions—the French Institute for Research and Development (IRD), the University of Nairobi School of Mathematics (UNSOM), Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), African Conservation Centre (ACC), and the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology—spoke both about the growing importance of modeling, and the budding collaboration between these French and Kenyan researchers. “We share one world, and the impact that each of us has rebounds through the whole system,” stated Dr. David Western, chairman of the African Conservation Center. “How do we understand our impact and mitigate it?” For Dr. Western, a conservationist who has been collecting data on large mammal populations and vegetation dynamics of Amboseli National Park for over forty years, the answer lies in forecasting and in anticipating problems through biomathematical models. Victor Mose, who has been collaborating with Dr. Western at the ACC-Amboseli Conservation Project, has constructed a model for large mammal population dynamics. His model can predict population changes under differing environmental conditions, such as drought. In presenting his work to the conference, Mose stressed that the model was not just esoteric. As he explained in his concluding remarks, “We can use this model to predict the situation on the ground and give the results to policy makers.” Mose and Josephine Kangunda, who presented her malaria model in an example of the epidemiological applications of biomathematics, are both products of the first National Biomathematics Workshop in 2009. As a result of their presentations at that first gathering, they were recruited as joint PhD candidates at the University of Nairobi School of Mathematics, and the University Pierre and Marie Curie (Paris 6) and University of Metz, respectively. Mose and Kangunda, along with Professor Charles Nyandwi of the University of Nairobi, and Dr. Jean Albergel, the IRD representative for East Africa, were the organizers of this second workshop. “There was a need to make the project continuous,” explains Mose. “We needed to train more Kenyans in biomathematics.” Their goal is to have annual three-week training sessions to educate French students in the ecology of Kenya, and Kenyan students in SciLab, an open source biomathematical modeling software package. The conference participants fully supported the proposal. Betty Buyu, director of ACC, was particularly impressed by the way that Mose and Kangunda “brought modeling alive to us”. She pledged ACC’s support in continuing to promote biomathematical modeling and its applications in Kenya to wildlife conservation. Professor Gauthier Sallet added IRD’s support. The French Ambassador to Kenya, Etienne de Poncins (who had invited all the workshop participants to his residence the previous night for a cocktail reception), promised “You can count on me,” as he urged that this interaction be seen in the context of a larger partnership between France and Kenya. The French Embassy, IRD, KWS, ACC and the Amboseli Conservation Programme provided support and organized the biomathematical workshop. AN UPDATE ON THE WILDLIFE AND LIVESTOCK PICTURE IN AMBOSELI BASIN

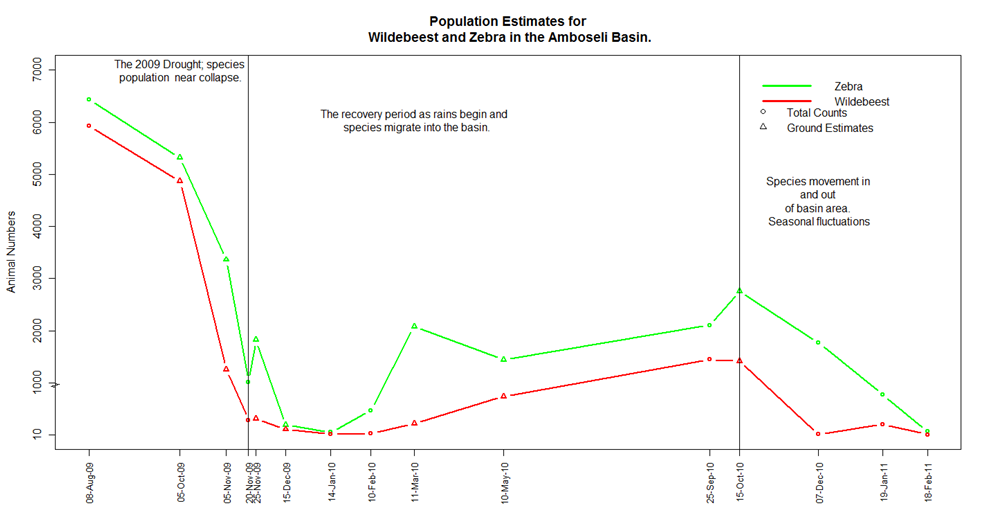

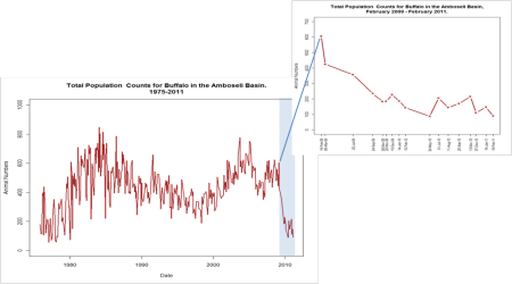

The restocking of wildlife numbers in Amboseli after the drought of 2009 was given an initial boost by the immigration of wildebeest and zebra from adjacent populations. The dry season following the drought, which left fewer than 300 wildebeest and 2,600 zebra out of the 7,000 or so starting numbers for each species, saw an influx of some 1,400 wildebeest and several hundred zebra from adjacent populations, most likely Tsavo and northern Tanzania. By late 2010, wildebeest numbers in Amboseli peaked at 1,400 and zebra at 2,700. Following the migrations out of Amboseli with the November-December rains, we expected to see larger numbers return following the birth season. As explained in the last report the unseasonal cyclone rains across the region kept the wildebeest and zebra populations out of the park and basin. Aerial counts of the park in February, the time of peak population numbers in previous years, showed the lowest wildlife numbers recorded in over 40 years. Wildebeest numbers dropped to 10 and zebra 71. Buffalo numbers fell from over 200 to 90. The extended migration lead to low populations in the park from November of 2010 to the dry season beginning late May of 2011, which put further pressure on the carnivore populations resulting in continued attacks on livestock by hyenas and lions. The eventual return of the migrations in June, seven months since its start, should have raised wildebeest and zebra numbers following the birth season. The first births in wildebeest and zebra after the drought occurred at the end of 2010 and early 2011, indicating that wildebeest and zebra took 3 months or more to recover before conceiving. We anticipated a 20 percent or more boost to the populations due to post-drought births. Surprisingly, the aerial and ground counts ACP conducted in July and August show the zebra population down this dry season, rather than up as expected. Zebra numbers fell from the 2010 peak of 2,700 to 1,800, despite the birth recruitment (Figure…..). The lower figure suggests that many zebra moved to other areas rather than return to the basin. Wildebeest populations remained about the same as 2010 (Fig..). A further 150 animals were counted close to the basin, giving a total of 1,550 compared to a peak of 1400 in 2010. This is a lower figure than the 1800 or so expected after the birth season, suggesting either a poor recruitment, heavy predation or fewer animals returning to basin. The picture for buffalo shows a somewhat downward dip in the population for the August dry season, from 210 at a peak in 2010 pre-birthing population, to some 185. Given that buffalo are relatively resident in the basin and environs, the indications are that the population has decline despite the post-drought birthing. The rains for the first half of 2011 were nearly as poor as the rains for the same period in 2009. FEWSNET, the early warning systems that predicted extreme droughts in the Horn of Africa this year, also predicted extreme droughts in the Amboseli region. This prediction, based largely on rainfall deficit, did not take account of the sharp fall off of grazing pressure following 2009 and so gave an erroneous prediction. In reality, the low herbivore populations in the basin due to the drought and the following extended migrations due to unseasonal rains in January, left abundant pasture in and around Amboseli. The condition of wildlife and livestock is good, despite the poor rains. A good amount of surplus grazing remains to the north of Amboseli, and swamp-edge pastures in the basin have barely been grazed since November of 2010. The Cynodon grasslands along the edge of Lake Amboseli that have supported large herbivore populations every dry season since the 1960s, are devoid of herbivores and support a dense matt of vegetation. The surplus grazing in Amboseli has spurred a rapid growth in sheep and goat herds among Maasai to make up for the collapse of the cattle herds in the 2009 drought. Numbers are up by a third since the drought, shifting the pastoral economy to a far heavier dependence on small stock than ever before. We expected a sluggish growth in cattle herds because of their longer gestation and slower growth rate, but did not reckon with the long distance restocking arising out of the emaciated herds in northern Kenya and Somalia. The good condition of cattle in Amboseli due to surplus grazing and the poor condition of the northern cattle and poverty caused by the extreme drought in the Horn has worked to the advantage of southern herders. Maasai in the Amboseli region have been selling their healthy cattle and buying up northern Kenya and Somali cattle at half the price. The 2:1 price advantage, the surplus grazing in Amboseli and the services of long-distance truckers and traders, is allowing the southern Maasai to restock their herds far faster than expected. There are three important points emerging from the ongoing ACP monitoring in the Amboseli Basin and across the ecosystem that reinforce the post-drought picture given in earlier reports. First, events driving the collapse of the herbivore populations in Amboseli and the rising carnivore-human conflict must be considered broadly. The prey shortages faced by lions and hyenas has been deepened by the unseasonal rains in January, the prolonged migration of herbivores and the poorer-than-expected numbers of wildlife in the August dry season. The behavior of the herbivores in response to higher predation risk appears to have a strong influence on their use of the basin and daily movement patterns in and out of the park. Second, the continued pressure on swamps and woodlands due to heavy use of the park by elephants will slow the recovery of habitats and drought grazing areas. This intensive use calls for an accelerated development of elephant exclosures to protect plant refugia and seed banks. Finally, close attention must be paid to the shifting social and economic patterns of pastoralism and large-scale movements of livestock into and out of the regions as a result of drought evasion, and to the new drought recovery strategies of trading fewer healthy cattle for drought-weakened animals from the north. The large-scale movements of cattle into and out of the Amboseli ecosystem reduces the impact on pastures during droughts on the one hand, but slows post-drought recovery of pastures on the other. Based on the long-term findings of ACP, David Western wrote a review of causes and implications of deepening drought in the pastoral areas of Kenya (reference to SciDev.Net). ACP staff have been attending emergency meetings called by the African Union and International Livestock Research Institute to discuss the worsening drought conditions in the Horn of Africa. The Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan (cross reference) is due for a 5-year review shortly. ACP will urge that the plan be reviewed in light of the drought and that heavy emphasis be put on recovery plans that address the underlying causes of habitat and species loss and the ecological dislocations aggravating human-wildlife conflict. THE FLUCTUATING FORTUNES OF WILDLIFE, PREDATORS AND PASTORALISTS IN AMBOSELI

In this report we review the counts of large herbivores in and around Amboseli National Park since the 2009 drought and consider some ecological and social consequences. The sample ground counts and total aerial counts (Fig. 1 and Fig 2) show the heavy drought losses wildebeest, zebra and buffalo, the main prey species of Amboseli’s large carnivores, suffered in the last four months of 2009 drought. The remaining herds moved out with the rains of December 2009, leaving a few dozen animals in the park. In the following dry season we had expected only the remnant herds surviving the drought to return to Amboseli. Quite unexpectedly, the remnant herds were accompanied by an influx of over 1,400 wildebeest and several hundred zebra from adjacent populations, most likely Tsavo and northern Tanzania. The herbivore populations built up to a peak of some 1,500 wildebeest and 2,500 zebra in the late dry season of 2010. During the November-December rains the numbers fell sharply again with the migrations. The migrants were expected back at the beginning of the dry season in January of 2011, but unexpected cyclone rains fell across the region and kept them out of the park in the wet season dispersal areas. Figure 1 Figure 2

The February total aerial count of the park gave the lowest wildlife numbers recorded in 43 years of ACP surveys. Wildebeest numbers dropped to 10 and zebra 71. Buffalo numbers dropped from over 200 to 90, meaning that more than half the population moved out of the basin with the unseasonal rains. Such an outward migration of buffalo from the park has not been recorded since the late 1960s and early 1970s. The March count showed little increase in herbivore numbers. The low counts mean that Amboseli is sure to skip the January to March dry season and that the migrations will extend from November until the end of the long rains in May or June. The long absence of wild herbivores will confront lions and hyenas with extreme food deprivation and raise the specter of conflict with livestock once more.

The extreme fluctuations in prey species in Amboseli since 2009, coupled with the longer term changes since the early 1990s, largely explains the growing conflict between large carnivores and Maasai herders around the park, as detailed in earlier reports. The precipitous drop in lion and hyena prey species in the Amboseli Basin since 2009 explains the sharp increase in carnivore-human conflict since the 2009 drought, as predicted at the Emergency Drought Workshop of December 2009. Carnivore attacks on livestock began immediately after the drought, coinciding with the wildebeest and zebra migrations and the return of the Maasai with their remnant cattle herds. At that stage, nearly all attacks on livestock were by lions unable to find wild prey in the vicinity. Contrary to expectations, hyenas did not attack livestock. They were getting by on the 10,000 or so carcasses left by the drought. The return of the migrant herds in the dry season of 2010, accompanied by an influx of animals from Tsavo and Tanzania, gave the carnivores enough to feed on without killing livestock. The drop in zebra and wildebeest numbers with the October rains of 2009 led to a further round of livestock attacks, this time with hyenas joining lions after they ran out of drought carcasses. A total of 274 livestock were killed by predators in September and October 2009. Hyenas killed 103 animals and lions 57. The unseasonal rains in February kept the migrant herds out of Amboseli, resulting in a continuation of carnivore attacks on livestock when they would otherwise have dropped off with the return of the migrants. The rising conflict between large carnivores and people in Amboseli is explained in large part by the collapse of their prey base in the 2009 drought. When the prey-based dropped by three quarters in a matter of months, the lion and hyena population would have dropped sharply in the following year was it not for the lion attacks on livestock and hyena dependence on drought carcasses. As it is, the lion population has fallen by nearly a half due to reprisal killing by herders. But several other ecological and social changes over the last two decades and more contribute to the ecological and social fallout of the 2009 drought. The most important factor explaining the rising attacks on livestock during the rains is permanent settlement. Until the early 1990s, Maasai pastoralists moved their livestock in tandem with the wildlife migrations—out of Amboseli with the rains and back in the dry season. Beginning in the early 1990s, the pastoralists around the park began occupying their seasonal settlements year-round. The upshot was that during the rains, livestock no longer migrated and were tempting prey for hungry carnivores. The shortage of wildlife prey during the rains was compounded by the sharp drop in resident browsing species in the park due to the loss of woodlands and woody vegetation. The losses of resident browsers exaggerated the shortage of prey during the migrations and made livestock more tempting yet to carnivores. Another factor contributing to the increasing carnivore-human conflict is the growing numbers of lions and hyenas in Amboseli. The numbers of wildebeest, zebra and buffalo in Amboseli more than doubled during the 1980s, giving the carnivores far more prey to feed on. Despite this increase in the prey base, carnivore numbers did not increase as quickly as expected. The main reason was that under the Wildlife Conservation and Management Department that ran Amboseli until 1989, anti-poaching was lax and little effort was made to prevent herders poisoning lions and hyenas. In 1989 when Kenya Wildlife Service took over management, security and conflict management quickly improved and carnivore numbers increased sharply. The growth in lion numbers that started with increasing security in the early 1990s increased yet again in the mid to late 2000s as the wild herbivore numbers concentrated more than ever in the basin due to intensifying drought and growing pasture shortages. The situation in Amboseli cannot be remedied easily, and certainly not by ignoring the root causes of the cause of the wildlife collapse and habitat degradation. It will take several years for wildlife and livestock numbers to rebound. In the meantime carnivore attacks on livestock will continue and perhaps increase if hyenas switch to stock killing during rains now that the drought carcasses have disappeared. That is, the attacks will continue unless prevented by barricades that KWS and conservation groups build around night corrals to curb predation. And if night corrals are successful carnivore numbers will drop to the size the wild herbivore prey base can support. Another factor that further complicates the picture is the response of wild herbivores to hungry carnivores. Zebra and wildebeest now regularly move out of the park at night. The nocturnal migration is something not previously seen in Amboseli. Coupled with a heavy exodus of zebra and wildebeest during the rains and the partial resumption of movement by buffalo not seen in decades, the avoidance of the park suggests that elevated predation pressure is a major deterrent. The interlinked ecological and social events driving the collapse of the herbivore populations in Amboseli and the tightening oscillations and rising carnivore-human conflict stress why the restoration and conservation of Amboseli must be considered broadly, rather than narrowly from the perspective of wild herbivores, carnivores or livestock. The fate of the carnivores is closely bound to the recovery of the wildlife herds and in turn the recovery of the rangelands, the Amboseli swamps and the woodland. The behavior of the herbivores in response to higher predation risk has a strong bearing on the level of use wildlife makes of the park, which will in turn affect the tourism appeal of Amboseli and perhaps visitation. The complex and continuing fallout of the drought and long-term habitat deterioration as well as changing social and economic situation among the Maasai in the Amboseli region calls for a reexamination of the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan. Habitat and species recovery plans will depend most of all on tackling the deep seated threats to the Amboseli ecosystem. |

NEWS FROM ACP

Find out about upcoming projects, events, and updates from ACP. Click here.

|

| AMBOSELI CONSERVATION PROGRAM |

|