In the case of the Coronavirus the blame lies squarely on the illegal trade in wildlife species, fueled by globalization. Diseases such as Ebola, Marburg and HIV erupted in small scattered communities in the past but remained localized epidemics. No longer.

In the last few decades, global travel has spawned virulent novel viruses such as SARS, MERS, H1N1 and COVID-19, infecting hundreds of millions around the world in weeks. These new pandemics are a grave threat to every nation, every individual. causing 6 of 10 infectious diseases, 2.5 billion illnesses and 2.7 million deaths each year.

The wildlife trade, worth $23 billion annually, operates largely underground like drug trafficking. And like the ivory wars which slashed elephant numbers across Africa from 1.2 million in 1970 to 450,000 today, the wildlife trade is driven by rising wealth in Asia. Hundreds of species of amphibians, snakes, fish, birds and mammals are butchered for the wildlife trade, among them bats, civets and pangolins suspected of transmitting lethal viruses.

We can’t be sure which species in the wildlife market in Wuhan sparked the COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless, the cramped confined conditions flouting concerns for animal welfare and human health, have unleashed the most devastating pandemic in modern times.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been dubbed the revenge of wildlife. Revenge it isn’t. Coronavirus smites indiscriminately. For every illegal trader infected, hundreds of millions of people are at risk, among them ardent animal lovers, doctors and nurses. Overlooked is the impact of the pandemic on wildlife.

Here’s why, and what you can do about it

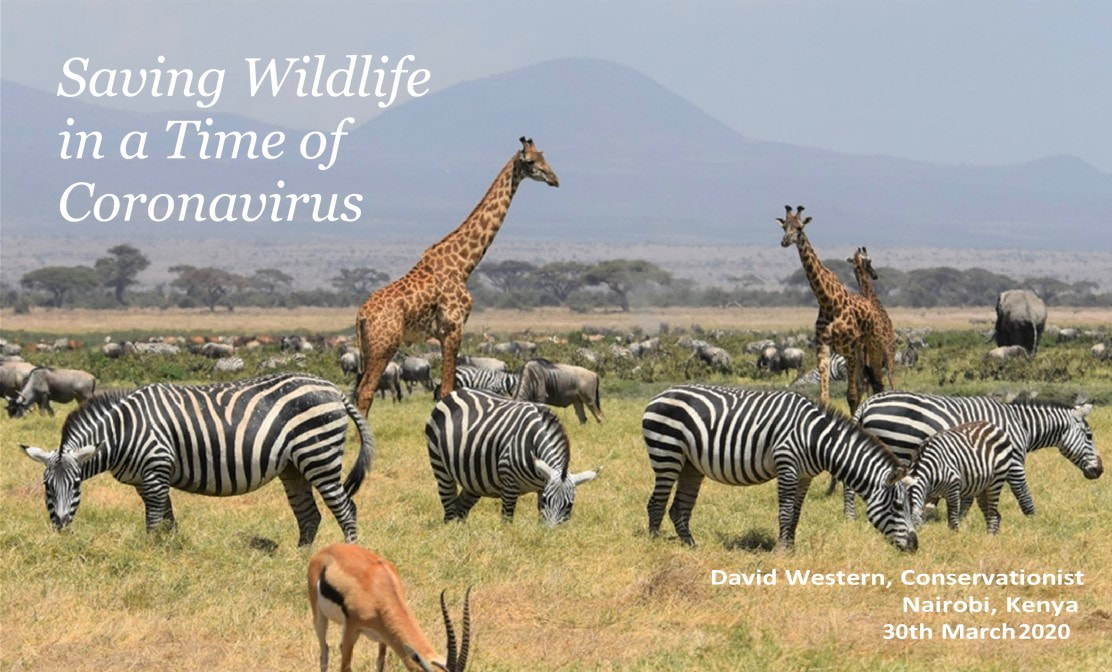

Community-based conservation is the greatest home-grown success in protecting Africa’s wildlife. Today, Kenya’s 150 community and private conservancies span 11 percent of the country, a larger area than all the national parks and reserves combined. Tanzania’s Wildlife Management Areas under local stewardship are playing an ever-growing role in conservation. In both countries, tourism is the engine of community-based conservation, creating thousands of jobs running ecotourism enterprises, deploying wildlife rangers and providing support services.

Amboseli, which pioneered community-based conservation in the 1970s, speaks to its success

The South Rift Association of Landowners joining Amboseli to Maasai Mara has shown similar success. The migratory herds and lion numbers have increased, and elephants have returned to the area for the first time in decades.

The collapse of tourism worldwide is disastrous for wildlife and community initiatives in East Africa. The shutdown at peak tourism season is closing lodges and wildlife enterprises overnight, and there will be no quick recovery. With the coronavirus causing a global recession, it will be many months before tourism recovers.

There are two things you can do to reduce the chances of further coronavirus pandemics and help conserve wildlife in East Africa

Second, help fill the void left by the collapse of the tourism industry in Africa. Wildlife tourism creates a virtuous circle. The visitor enjoys the safari of a lifetime to the greatest wildlife spectacles on earth, creates jobs and opportunities for communities, and wins a place for wildlife.

For the hundreds of thousands of visitors who‘ve had to cancel or defer safaris, a small portion of the savings made as a conservation contribution will make a world of difference. For others unable to make a wildlife safari, a contribution to community-based conservation helps support the custodians of wildlife.

A lion is worth ten times more alive through tourism than supplying claws to the wildlife trade. Stopping the wildlife trade and supporting community programs will help prevent another pandemic and save wildlife.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed