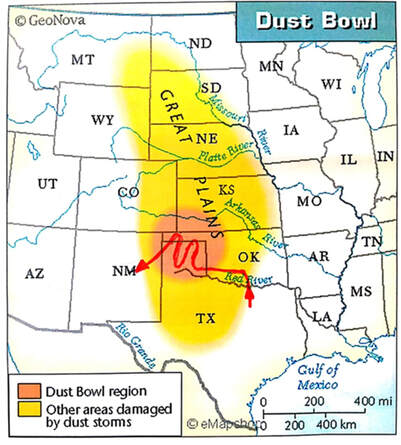

My route ( in red ) through the heart of the 1930s Dust Bowl region centered on the Oklahoma-Texas Panhandle.

My route ( in red ) through the heart of the 1930s Dust Bowl region centered on the Oklahoma-Texas Panhandle. I wrote a couple of articles in Kenya’s Nation newspaper during the 2000 millennium drought warning of worse times to come unless we took steps to arrest the impact of land subdivision, settlement and farms on the pastoral and wildlife lands of the East African savannas. In the coming years as the degradation worsened and droughts intensified, I pointed to the lessons we could learn from the tragedy of American Dust Bowl in the 1930s.

Timothy Egan’s The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl is a fine first-hand account told by the survivors. The Great Plains—the American Serengeti as it has been called--had for millennia been home to millions of bison, elk and prong horn antelope and the Comanche, Arapaho and other tribes who hunted them.

The high plains in the southwest were the last of the American prairies to be carved up and handed out to homesteaders in late 19th century. Following the extermination of the bison and incarceration of the plains Indians in reservations, homesteaders lured by cheap land, ready bank credits and a quick fortune from the booming wheat and cattle markets arrived in the tens of thousands to farm the prairies.

The story goes that cattlemen and farmers—sod-busters as they were called—settled the plains in a wet period, overused the land and destroyed the grass cover binding the fragile soils.

The wheat and cattle boom deflated with the return of dry years and plunging crop and beef markets. Farmers plowed more land to cover their loses and by 1934 the barren land began to lift, creating huge dusters, black blizzards and drifting sands. Over 2 million people were displaced in a humanitarian disaster that helped topple President Herbert Hoover and usher in F D Roosevelt who mobilized thousands of young men to plant trees and stabilize the prairie soils.

What had happened to the degraded land since the Dust Bowl era? What became of the family farmers, herders and wildlife? And what lessons did the prairie Dust Bowl offer the African savannas?

This was a story worth pursuing, yet oddly I could find little about the Dust Bowl or the settlers after the tragedy. In March of 2019 I paid a visit to the Texas-Oklahoma panhandle at the epicenter of the disaster to find out. My drive took me through the worst hit of the Dust Bowl regions—Arnett, Shattuck, Higgins, Glazier, Canadian, Miami, Pampa, Amarillo, Channing, Dalhart, Boise City, Clayton and Springer.

I start out from Norman south of Oklahoma City and travelled along route 40 where the land turns drier, the grasslands sparser and the ground barren. In Clinton where I stop off to refuel, the town, like others along the route, is shedding population and businesses like autumn leaves and homes are decaying like inner-city ghettos. Half the stores and businesses in Elk City, where I haul in for coffee, are shuttered. A solitary visitor drops by in the half hour, I spend chatting to the owner. Sayr, where I turn north onto 283, is ghostly quiet. The stores on the main street are derelict. All but two gas stations are boarded up for lack of custom. At the historical museum, General Custer is more celebrated than the homesteaders who survived the Dust Bowl tragedy and the first settlers, the Indians who occupied the Great Plains for millennia beforehand.

On the drive through Black Kettle National Grassland reserve, I pass through areas heavily battered and degraded in the 1930s. Dozens of farms are abandoned, homes are crumbling, and fields are being recolonized by bunch grass and scrub too coarse and dry to see a cow through winter. The small holdings have been bought out by large farming conglomerates which have defeated the hostile climate by drilling deep down to the Ogallala Aquifer and using the energy of fossil fuels pumped from yet deeper into the earth to power huge articulating irrigation booms which water circular fields of cattle fodder, maize, wheat and cotton. Oil rigs by the hundreds dot the farmlands and supplement corporate incomes from corn and beef trucked to distant American families. Despite its name, Black Kettle Grassland has restored little natural grassland. Large irrigated farms blanket the landscape and dwarf the national grasslands bought up by Roosevelt during the New Deal to relieve destitute farmers.

Up the road from Channing hay fields give way to corn as I approach Dalhart. Dalhart, sitting at 4,600 feet above sea level, averages less than 14” of rain. Unlike the tropics where rainfall increases with altitude, the cold and wind of the high plains shorten the growing season. It takes deep corporate pockets and oil from dozens of rigs to capitalize the heavy-duty tractors, combines and fertilizers needed to grow a bounty of corn and wheat in an area where American family farmers failed to make a living in the Dust Bowl days.

I drive to Boise where only a few scattered tracts hint at the once endless prairies among the large commercial farms. I spot only two herds of prong horned antelope in the remnant grasslands where tens of thousands once roamed. My next stop, Boise City, is fast becoming a ghost town where hospitals, churches, meeting halls and whole streets are abandoned and shuttered. The town is graveyards of old cars, truck, tractors, combine harvesters and metal grain silos. Like so many dying towns in the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandle, human graveyards are filling up as the towns empty out. How sad and morbid driving past the derelict homes of families who once worked the land, loved, married, and raised children here, only to watch their way of life vanish and their youngsters move to the cities.

I check into the Kokopelli Lodge in Clayton for the night after driving through intensively irrigated flat and featureless land with not a tree in sight, except where some homesteader planted a few as windbreaks around a small clapboard cabin. Today the houses are few and far between and sizeable, used by managers who tend the farms and drive the plant. With every aspect of farm production, harvesting, marketing and distribution closely monitored and analyzed by GPS devices and computer programs, farming today is technocracy rather than husbandry.

Nearing Clayton, I turn off the highway to check out a vast feedlot of some 10,000 cattle packed belly to belly in 50 acres of paddock. “This is the dinner you eat,” reads the sign at the entrance to the factory farm. The stench is so strong from the slop of mud and dung that I stop for a quick snapshot and rush on for fresh air. If the smell was served up with every slab of beef and hamburger in homes and restaurants, America would banish factory farms.

Clayton, unlike the other victims of depopulation on the High Plains, shows signs of renewal among the shuttered buildings as visitors keen to get a feel of the pioneer days stop by overnight.

The drive to Springer climbs steadily to 5,800’. Extensive grasslands stretch to a low ridge of hills to the north. The scene resembles Serengeti looking across to the Nabi Hills, the more so for a herd of pronghorn antelope grazing the shortgrass plains. The plains are the epitome of the abandoned dust bowl scenes, minus the wind-swept sands. Widely scattered abandoned homes with a few spindly trees and crumbling windmills dot the high plains. Life must have been a lonely and spartan for the Dust Bowl survivors who hung on after the destitute families drifted away. The ranches nowadays run to thousands of acres with barely a cow and never a herder in sight. I don’t see a single person on the 60-mile drive to Springer at the end of my Dust Bowl tour with much to reflect on.

The damage caused by the spread of European colonialism around the world and across the US prompted President Roosevelt to convene the Conference of Governors on the Conservation of Natural Resources in 1908. In his opening address he asked, “what will happen when our forests are gone, when the coal, the iron, the oil and the gas are exhausted, when the soils shall have been still further impoverished…We began with soils of unexampled fertility land, and we have so impoverished them by injudicious use and failing to check erosion that their crop-producing power is diminishing instead of increasing.”

Yet the very next year, in 1909, a Soil Bureau’s statement read: “The soil is the one indestructible, immutable asset that the national possess. It is the one resource that cannot be exhausted; that cannot be used up”. This view was contested by experts, including High Hammond Bennett, who warned of the devastation homesteaders and farmers would cause on the high plains, and with good reason. The grasslands rise from 2,000’ to over 6,000’, have sparse sporadic rainfall, periodic droughts, searing heat and hurricanes in summer and bitter cold spells and blizzards in winter. The plains are treeless and parched dry most of the year with little drainage or surface water. Most rains fall in spring and summer when high temperatures and wind reduce infiltration and water-use efficiency.

The plains in the heyday of the bison herds were dominated by grama-buffalo grass, wire grass, bluestem bunch grass and sand grass-sand sage. The soils are largely loess, remnants of the windblown soils of the post-glacial period held in place by an overburden of thin organic soils bound by plant roots. Beneath the loess is a minerally-leached calcareous hard pan. The roots trapped the moisture and held the soils in place during the heavy seasonal grazing by migratory buffalo herds. The desiccation of plant and water would have given the grasses a long rest period after the bison retreated to their winter grounds.

Despite the warnings, the federal government was so intent on exploiting the last of the open prairie lands after the army defeated the Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne and Arapahoe that it granted 320 acres of land to settlers under the Enlarged Homelands Act of 1909. Ignoring the marginal conditions, hostile climate and vulnerability of the high plains to overuse, settlements in the Llano Estacado in eastern New Mexico and northwestern Texas doubled between 1900 and 1920 and accelerated again in the 1920s with a rise in cereal prices on the world market and a run of good rainfall years. Hannah Holleman in her recent book, Dust Bowls of Empire, agrees with Donald Worcester’s classical account in Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s: the immediate causes of the Great Plains disaster were market forces, tenant farmers replaced by mechanization, overextended credit, injudicious land clearing and farm practices, drought and the natural vulnerability of the high plains—the ultimate forces capitalism and agro-industrial farming.

The phases of agricultural intensification are still detectable in the dilapidated homesteader shacks, in the farmhouses of wealthier ranchers and farmers who bought them out, and in the industrial farms with their giant pivot irrigation booms watering fertile fields of hay and corn. Industrial farming favors big corporations able to invest in heavy equipment and ride out lean years. I doubt they would make a go of it either without the extraction of voluminous flows of water from the deep aquifers made possible by cheap oil and farm subsidies paid for by the American taxpayer.

The towns in the Dust Bowl region grew with farm production on the high plains, only to fall on hard times when agrobusiness moved in and cut the labor force to the core. Today the towns no longer have the population or tax base to keep schools, libraries, and fire stations open, or maintain the roads. The remaining residents are aging and struggling to hold on. Their homes are falling into disrepair, barely distinguishable from abandoned houses. The dying towns are graveyards of rusting farm machinery and acres of abandoned cars.

What of the future?

The Dust Bowl 80 years on is carpeted over with greenery, insulating the earth from the wind-blown erosion. Large areas no longer farmed have reverted to grass and shrub cover reminiscent of the bison prairies though no native in composition. Dust storms may recur in extreme years, and have a few times since, but only locally and with nothing like the severity of the Dust Bowl era than blew away 75 percent of the topsoil.

The Dust Bowl was a product of its time, a conflation of human hubris, ignorance, and extreme drought. The land parcels were too small for family farmers to make a living, let alone better lives. Farm technology was a case of too much horsepower for the good of the land in the hands of farmers who lacked familiarity with the earth. Ironically, it took yet more technology, energy and capital to make the land productive. Agro-industrial farming today has turned a disaster zone into a breadbasket and feed lot for urban America.

I read Donald Worcester’s classic Dust Bowl after my trip to the Oklahoma-Texas Panhandle and agreed with his conclusions after revisiting the area where he grew up:

“Capital-intensive agribusiness had transformed the scene; deep wells in the aquifer, intensive irrigation, the use of artificial pesticides and fertilizers, and giant harvesters were creating immense crops year after year whether it rained or not”. According to the farmers he interviewed, technology had provided the perfect answer to old troubles. The bad old days will not return, they insist. In Worcester’s view, by contrast, the American capitalist high-tech farmers had learned nothing. They were continuing to work in an unstainable way, devoting far cheaper subsidized energy to growing food than the energy could give back to its ultimate consumer”.

It seems to me the corporate farmers are also a product of their time, sustainable only as long the oil, aquifers and government subsidies last, the present climatic conditions hold, Americans continue to eat 50 pounds or more of beef each year, and are willing to tolerate the cost of leached fertilizers and pesticides into the landscape and rivers and greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. When subsidies, diets and climate changes and aquifer sink to uneconomic levels, the high plains will change once more. The future is already emerging in new wind and solar farms and with the new nature sensibilities that attract visitors to enjoy the vastness of the Great Plains and its history.

Are there lessons from the Dust Bowl for the savannas now being subdivided, privatized, and settled? I think so, in several ways. Perhaps the most important is to recognize that land as a commodity rather than the foundation of a communal way of life that has sustained East African pastoralists for generations is liable to the vicissitudes of market forces and short-term gains. The savannas are in the process of becoming market producers of beef and grain rather than family sustenance and welfare. As in the Dust Bowl, the private allotments are far too small to support a family. Cattle barons land speculators are eying the fallout of subdivision and degradation. The same exodus of dispossessed families is underway.

It will take the resident families banding together as producer associations and land trusts to use the land sustainably for the benefit of its resident members. Even then, a large-scale emigration from the land to the cities is inevitable in the coming decades as the population grows larger than the land can support--and the younger generation seeks new opportunities. Education is key to providing a passport to opportunities elsewhere. There is also an urgent need to restore the rotational use of grasslands that sustained pastoral livestock and wildlife for millennia in the East African savannas and to embark on a restoration program for the degraded lands, much as Roosevelt did in the Dust Bowl era.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed