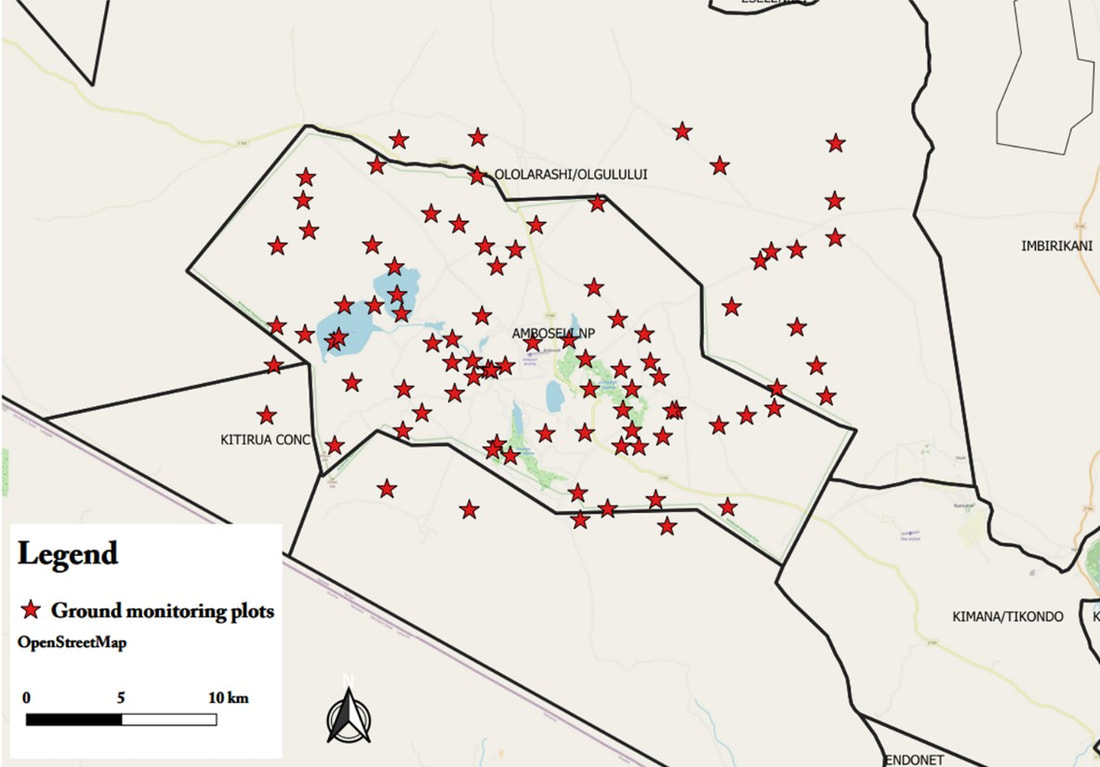

Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) has been working closely with many partners over the past two years to forge conservation coalitions able to monitor Amboseli and southern Kenya landscapes. The aim of the coalitions is to keep the rangelands open and viable for wildlife and pastoral livestock. Covid-19 slowed the enthusiasm and momentum built up in 2020.

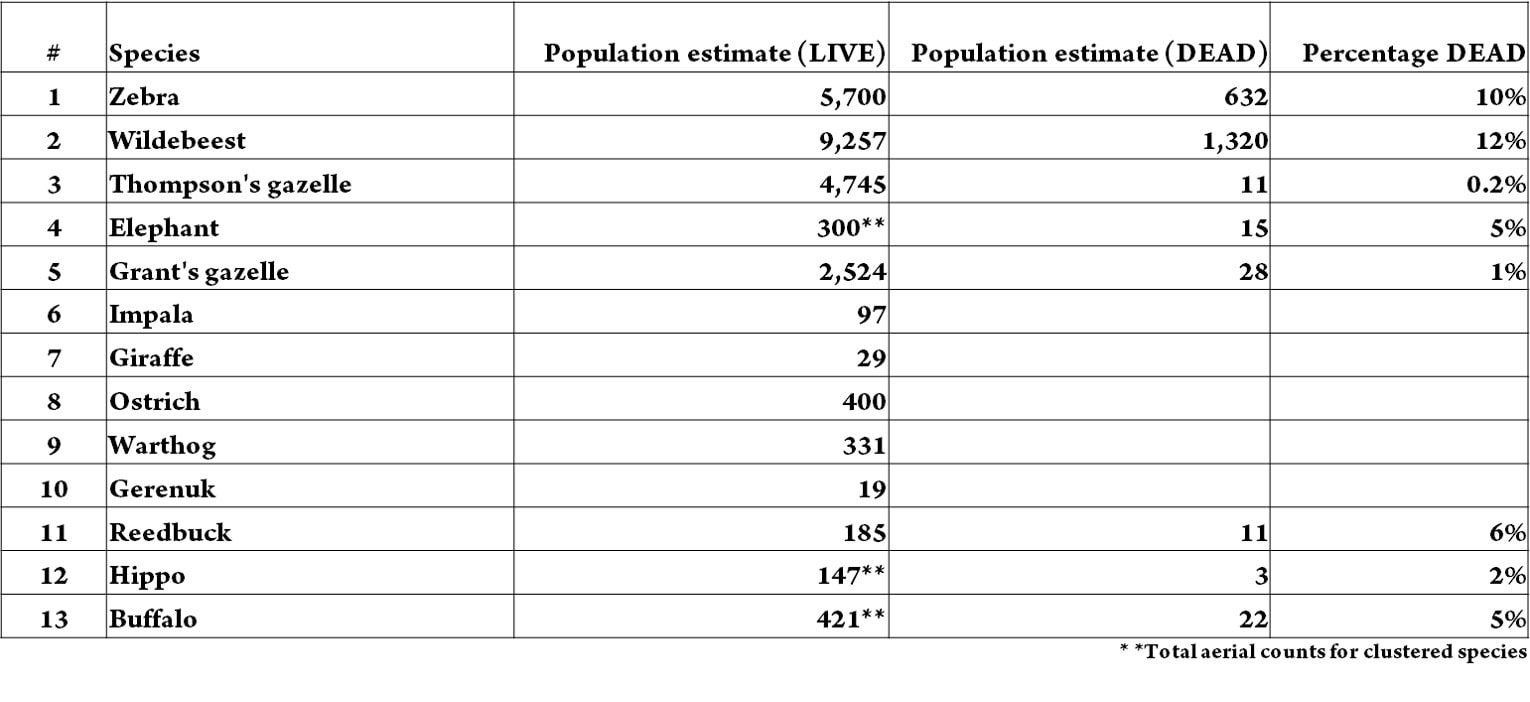

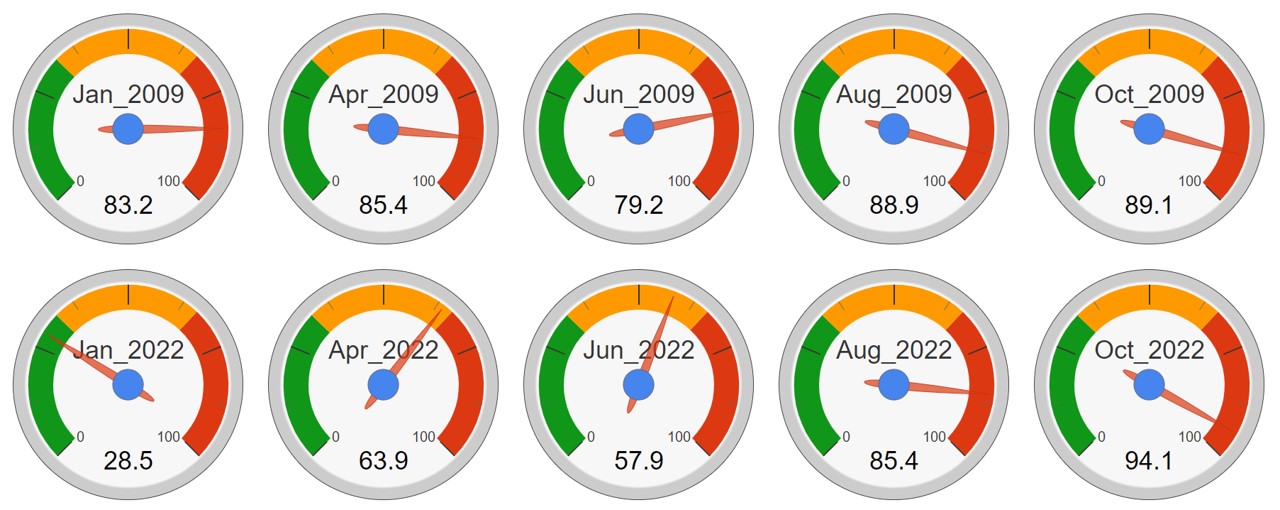

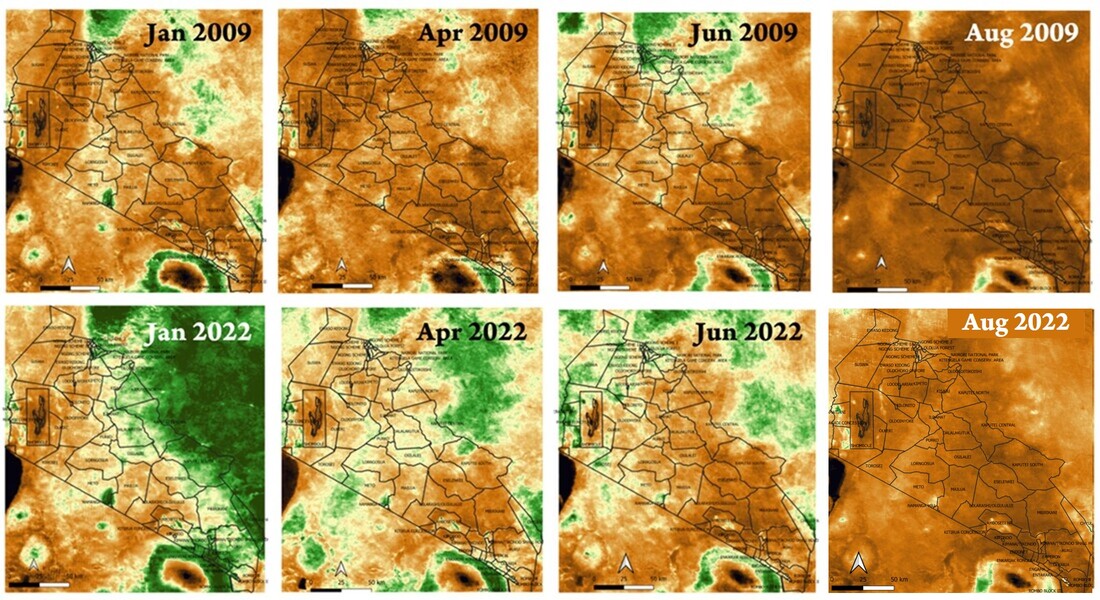

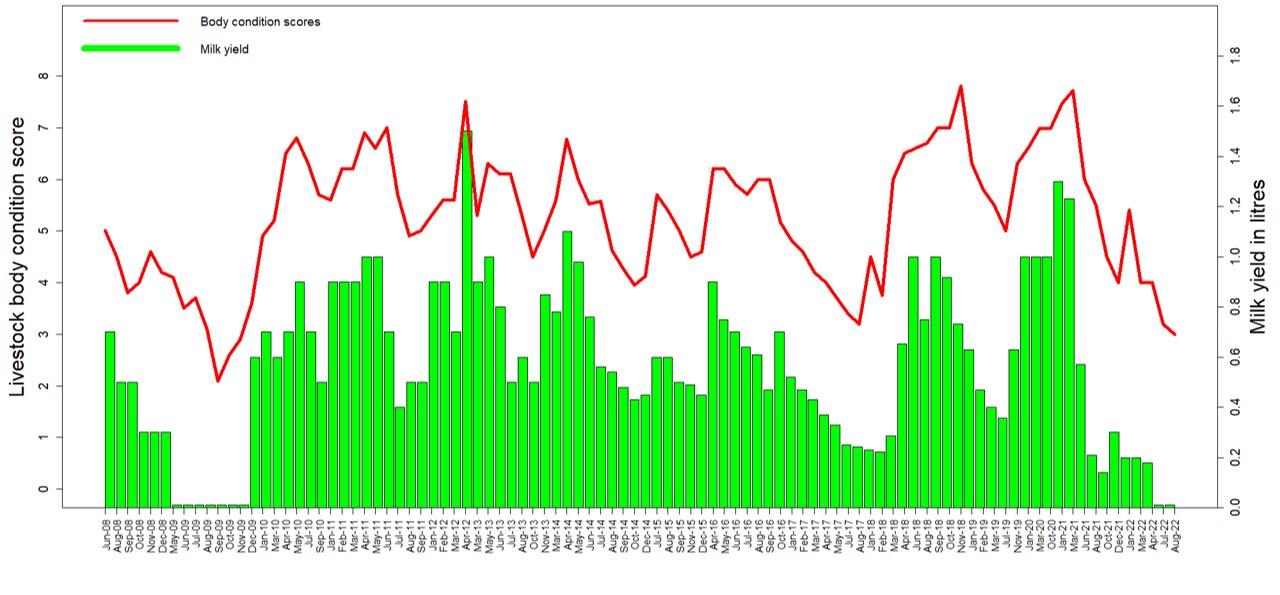

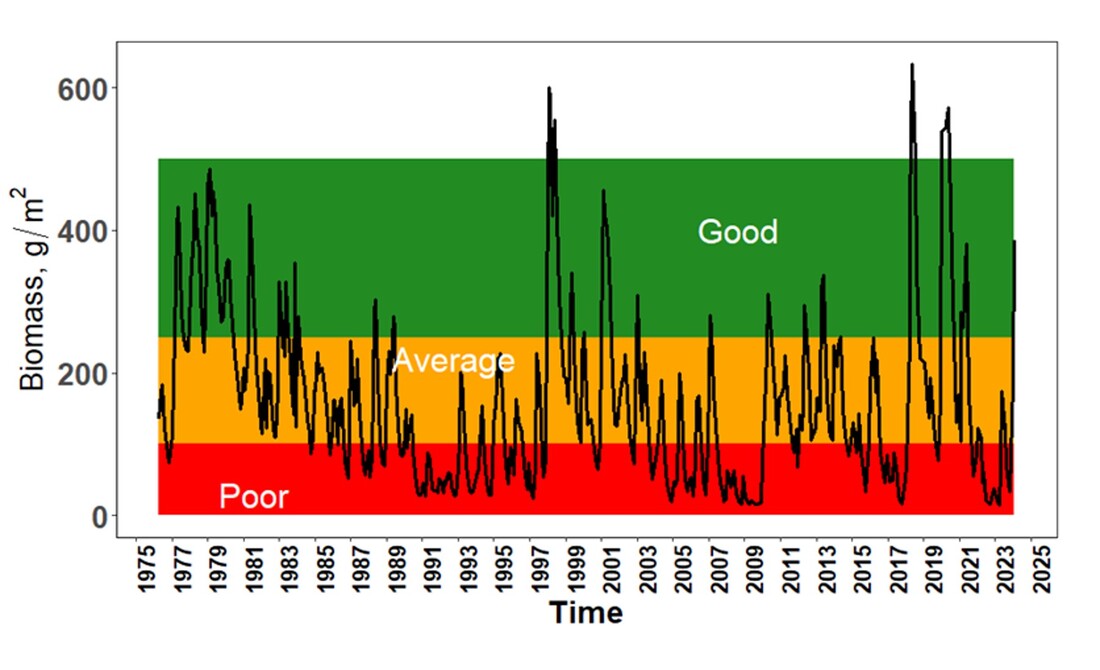

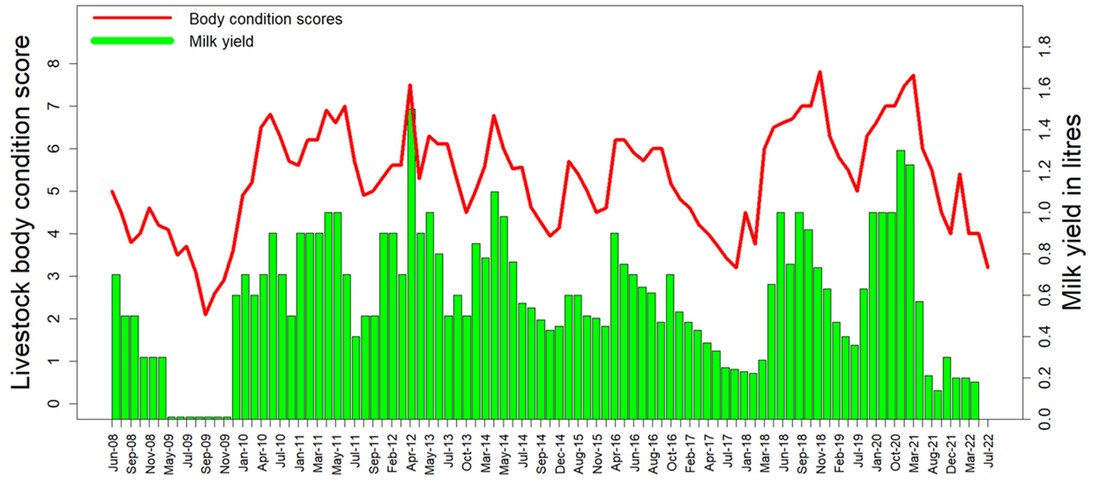

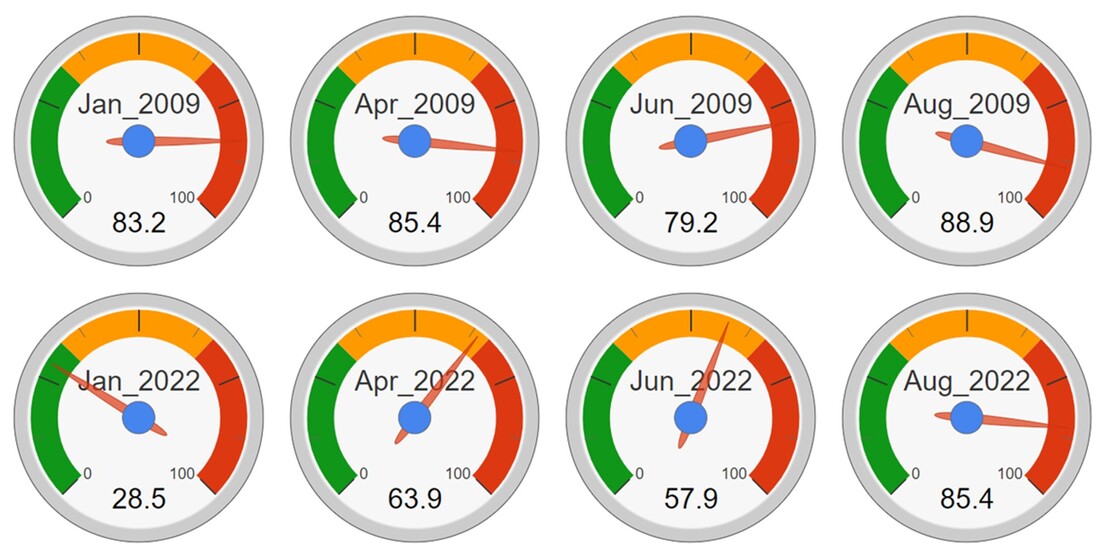

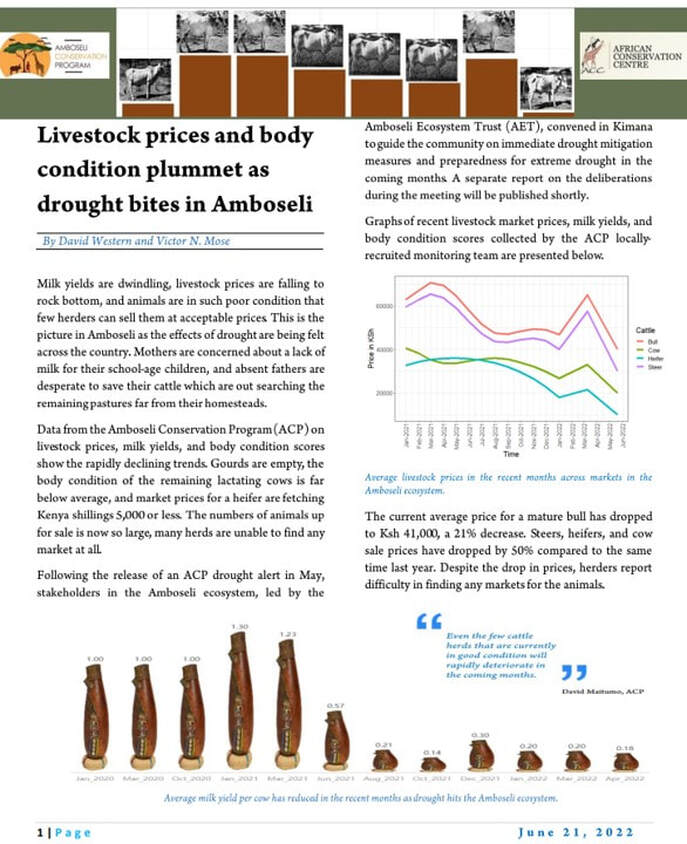

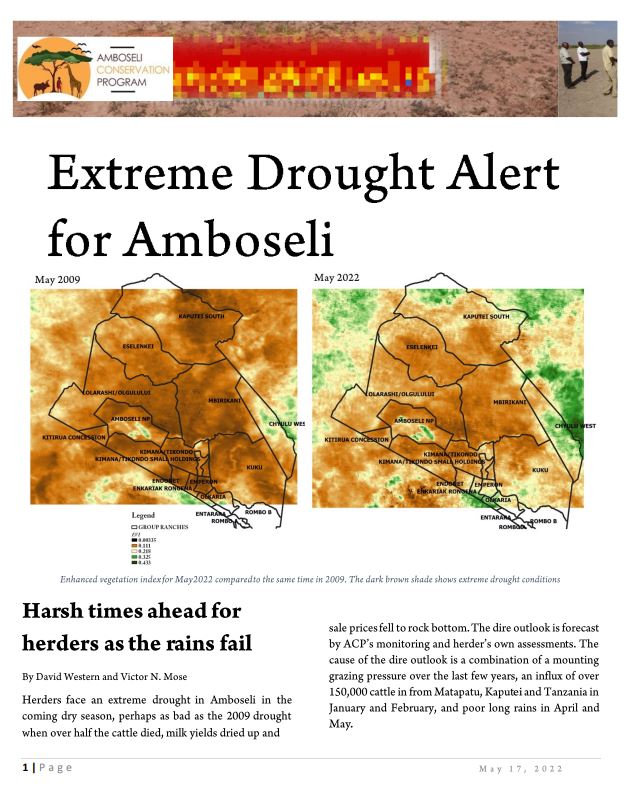

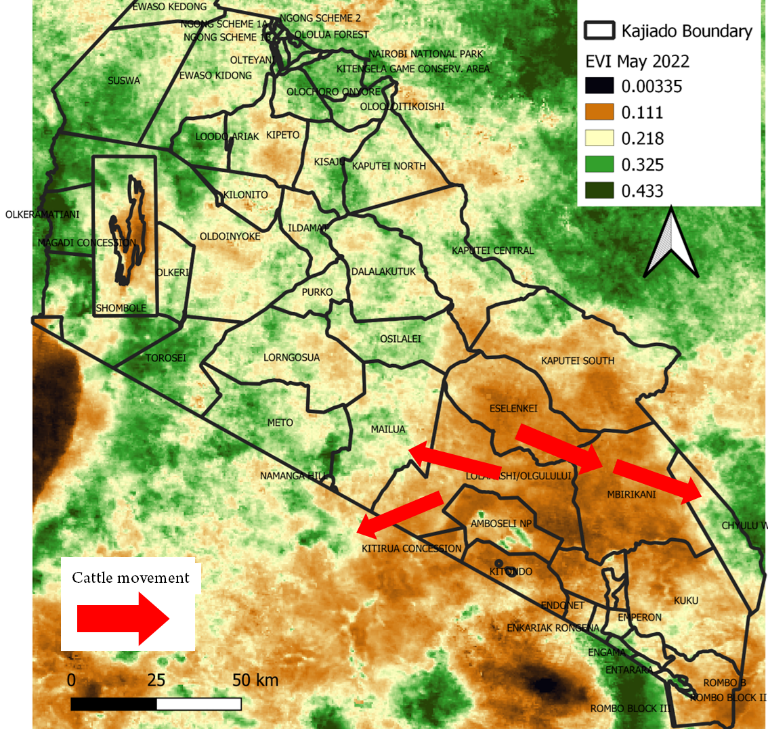

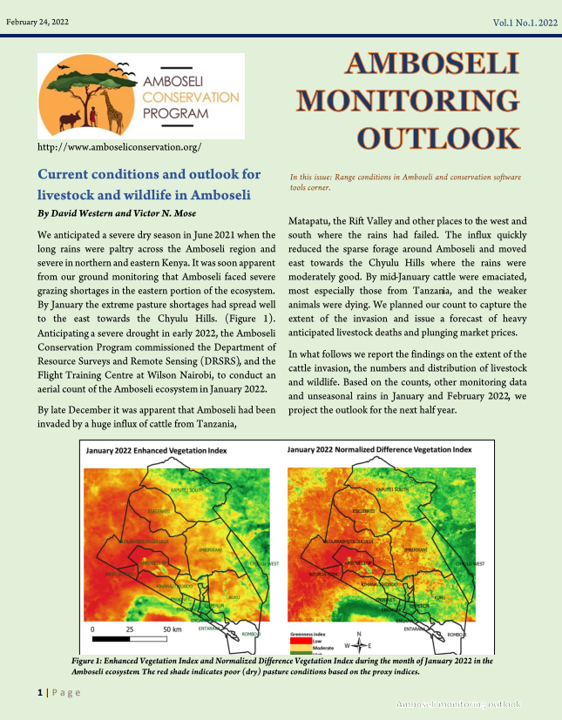

At both meetings ACP gave presentations on the build up to the intensified droughts and floods in Amboseli, and the ecological dislocations across southern Kenya. Both meetings called for information platforms to track and monitor the rangelands, issue early warning alerts, and communicate the information for AET and SRC to plan and manage the rangelands more effectively in the face of land use and climate changes.

The results of both the AET and SRC meetings can be downloaded below.

| aet_workshop_report.pdf |

| report__src_aet_worskshop.pdf |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed