Introduction

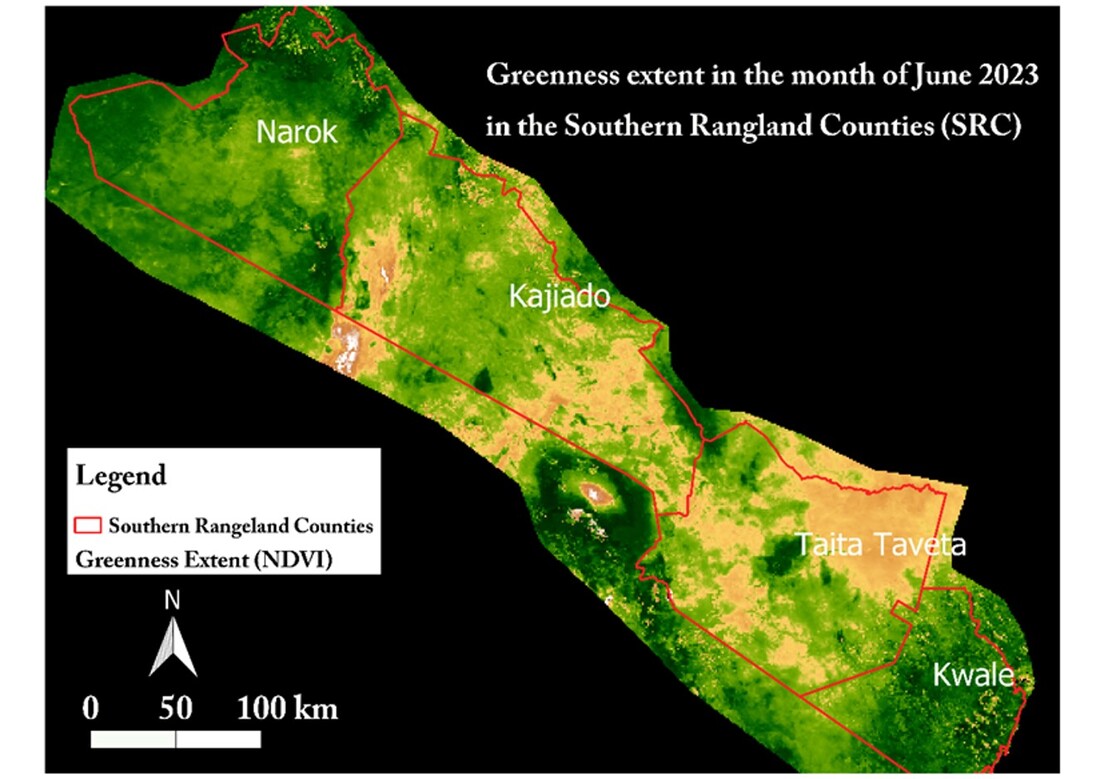

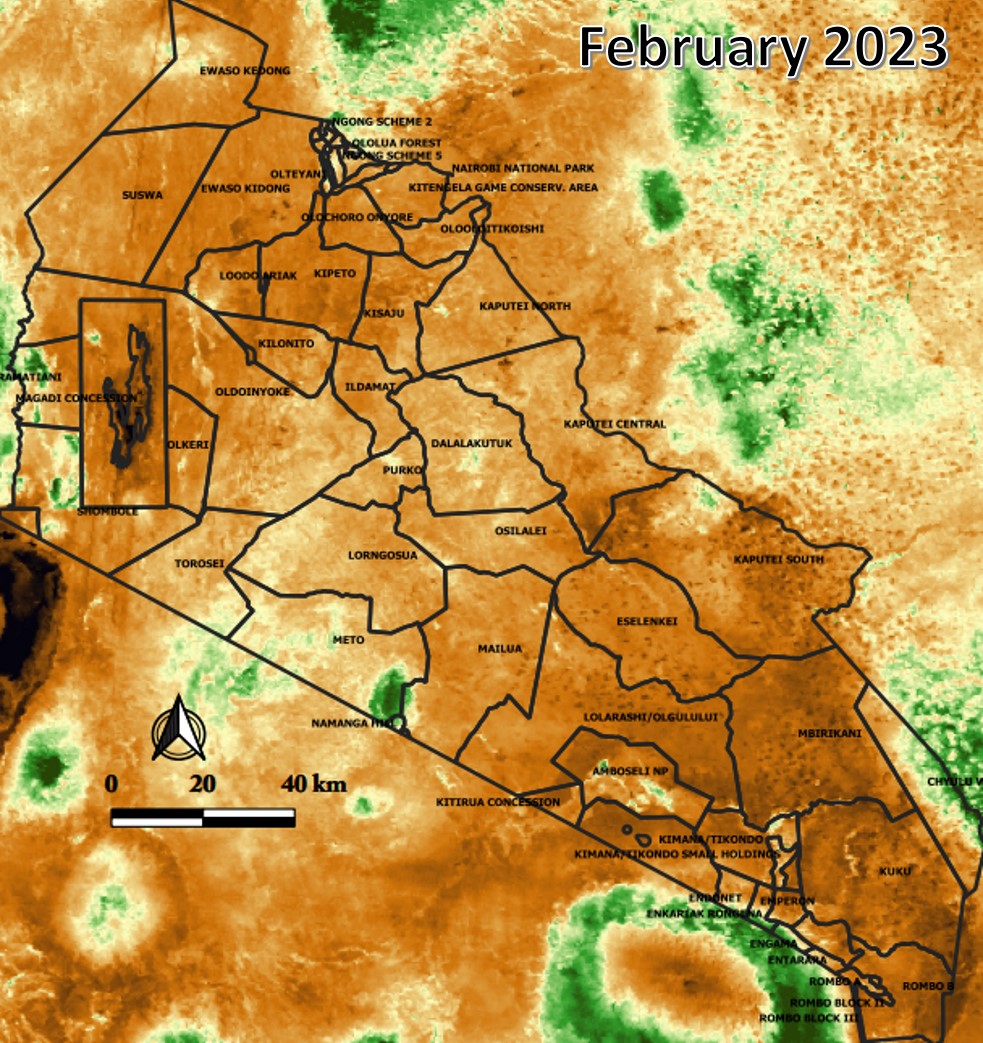

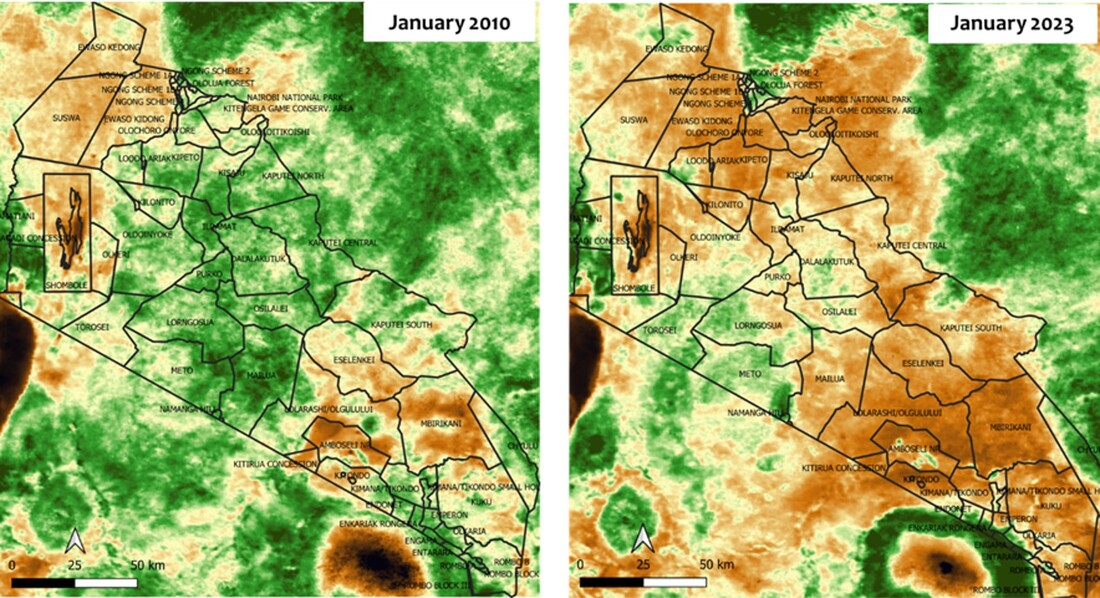

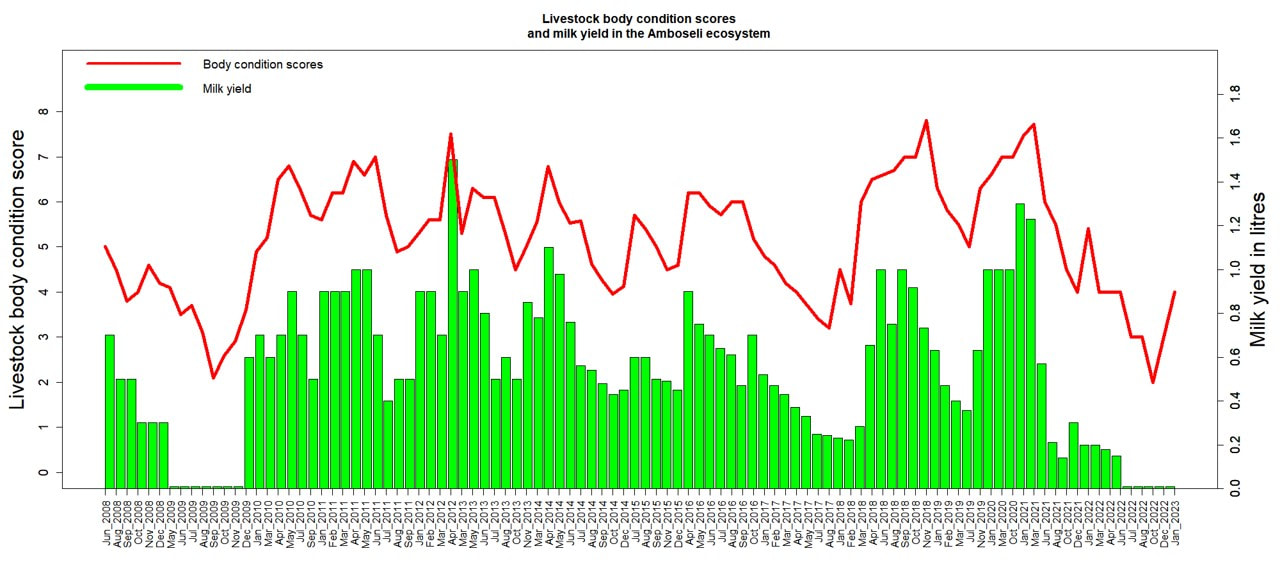

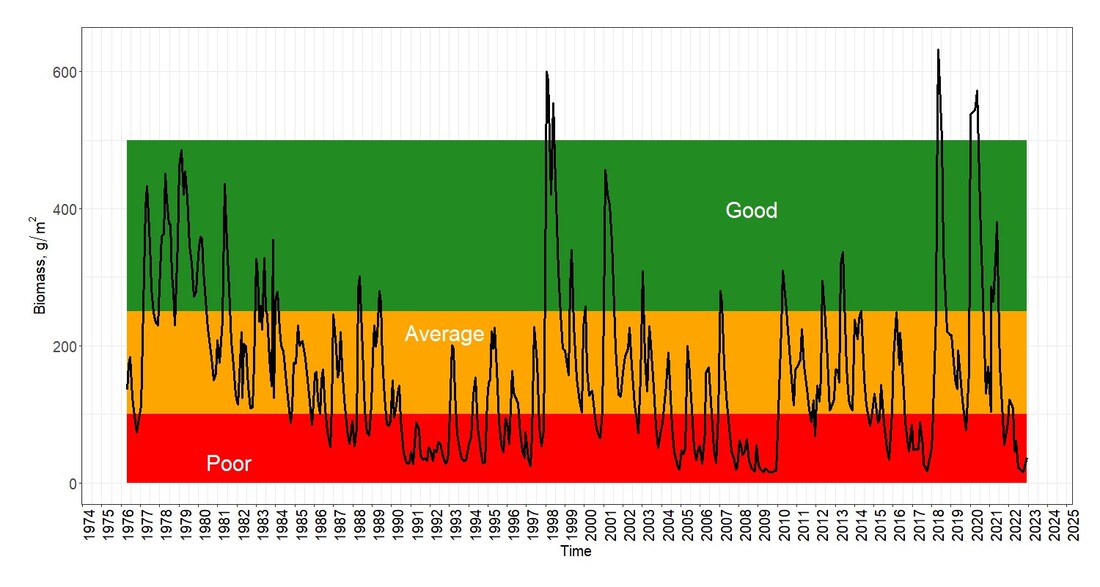

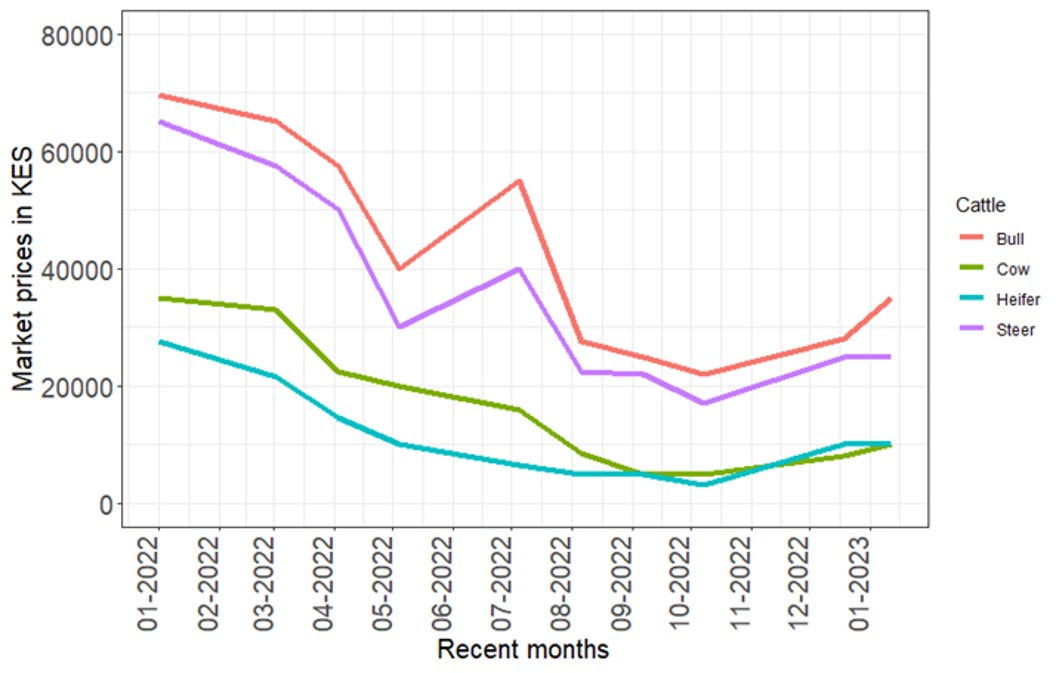

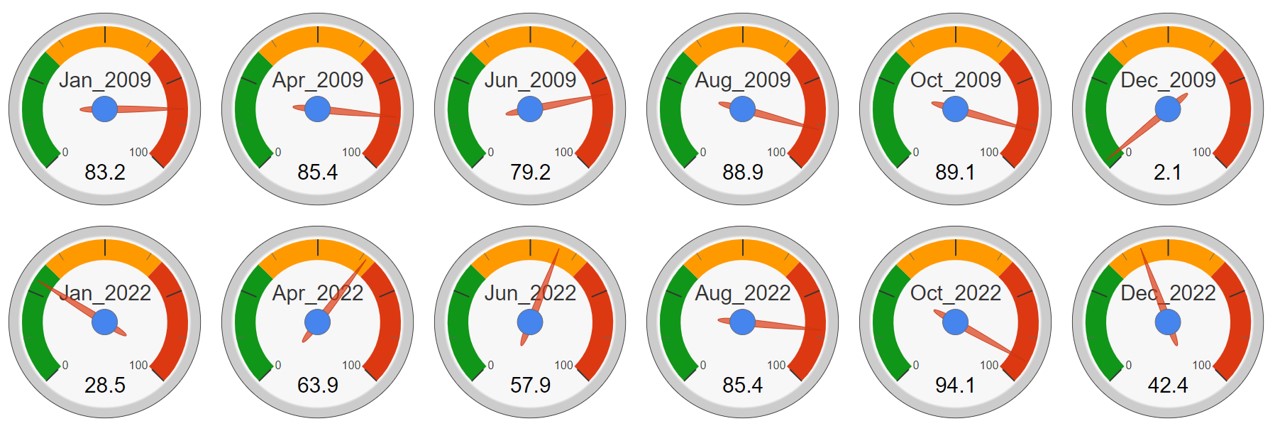

This ACP report is one of our regular series tracking the conditions of the rangelands, pastoral economy and wildlife in Amboseli. We also give pasture conditions across the southern region from Narok to Taita-Taveta which may dictate cattle movements across the region this dry season.

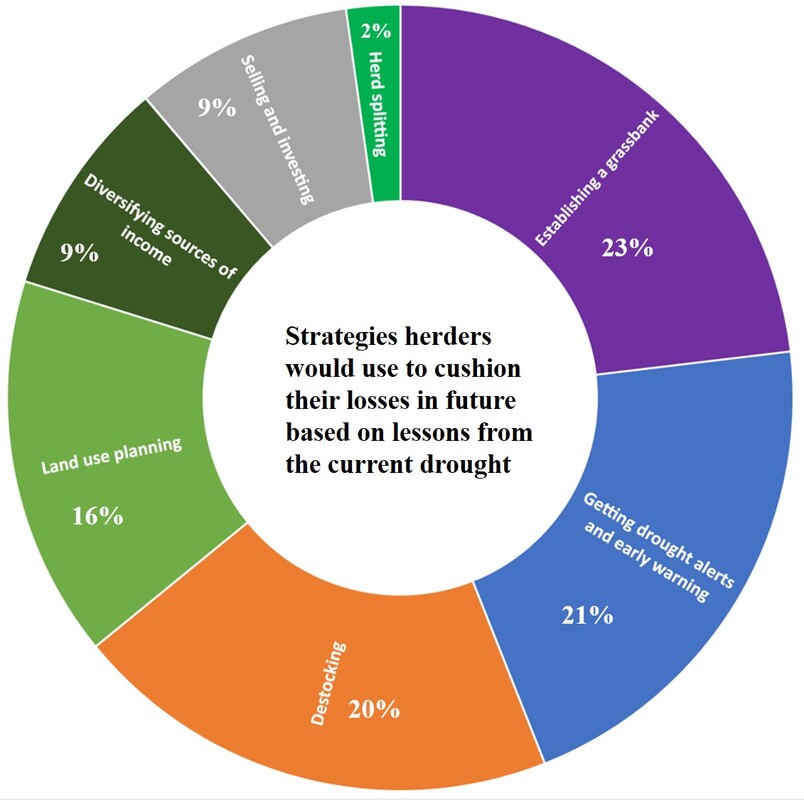

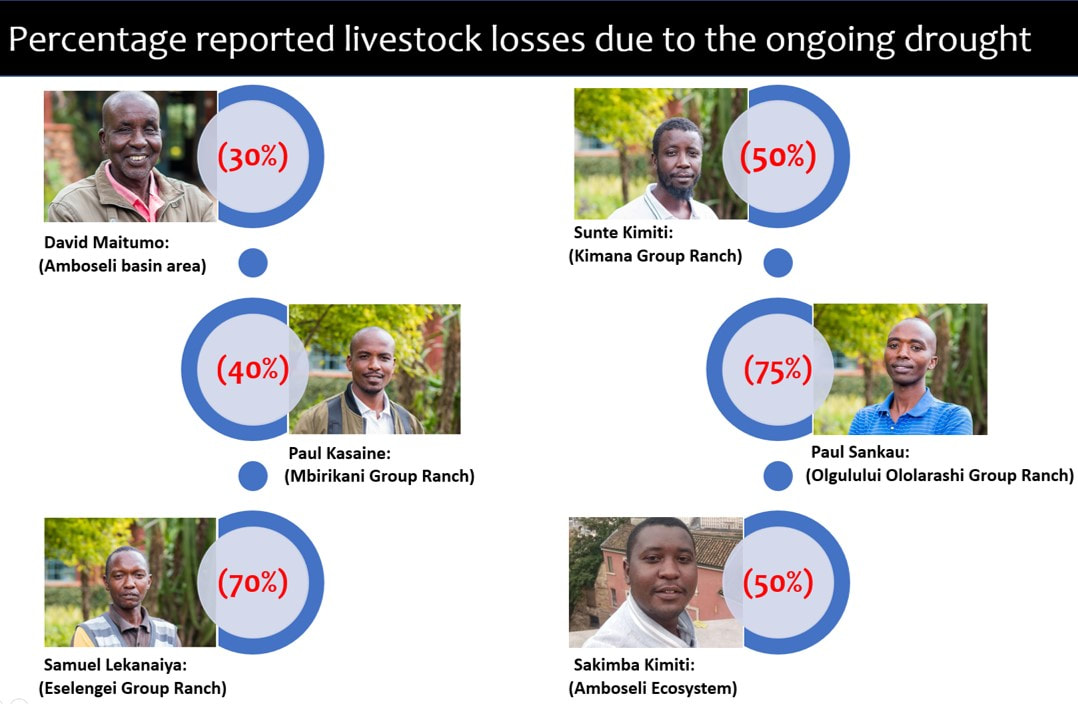

Our report shows that pasture and livestock conditions have not recovered sufficiently with the long rains to avert harsh conditions until the short rains late in the year.

| amboseli_post_drought_report_acp.pdf |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed