Introduction

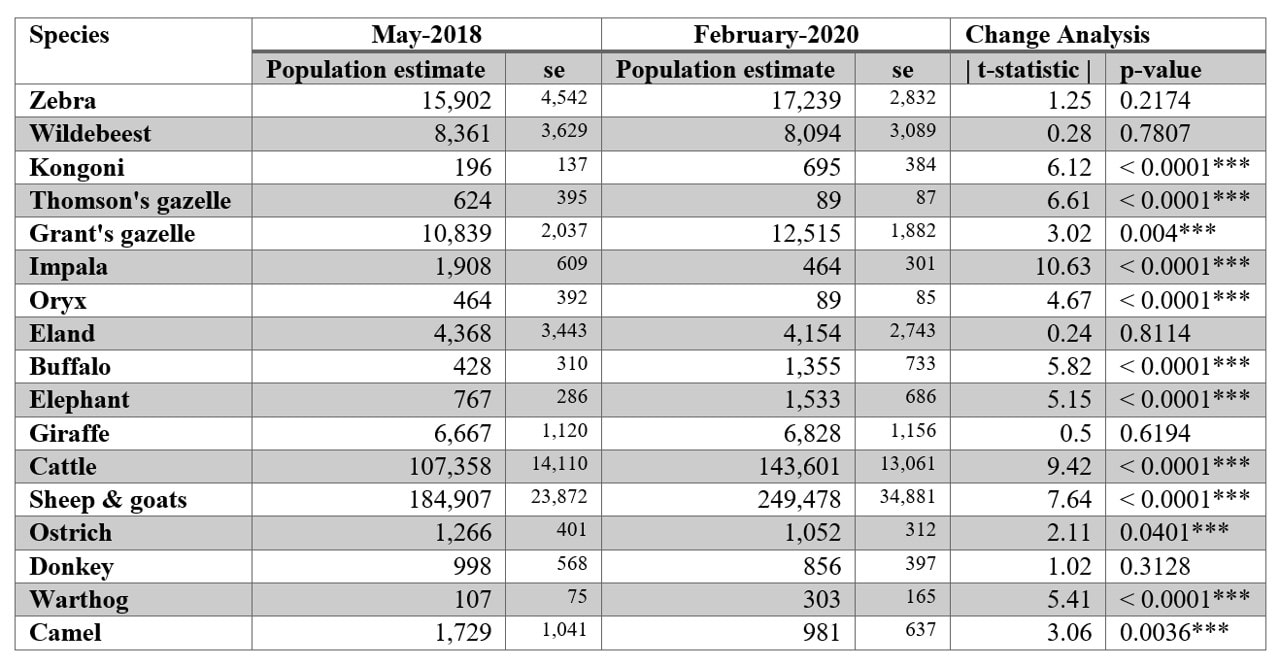

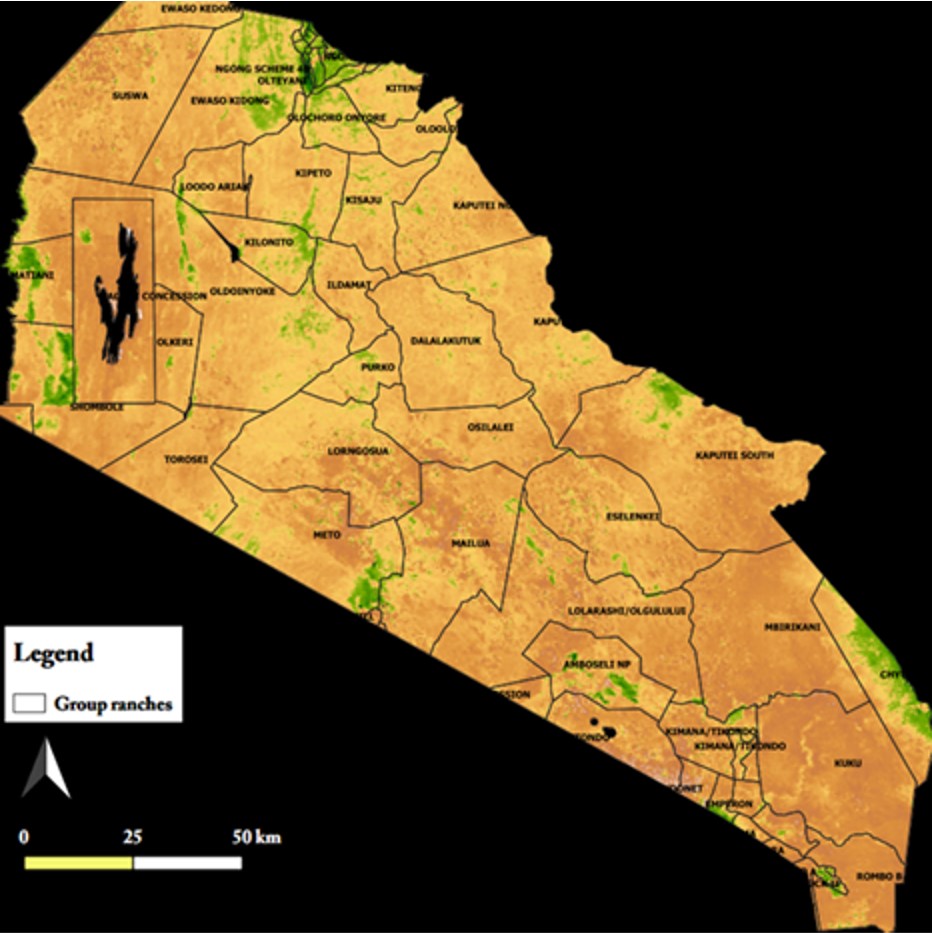

The Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) has conducted regular aerial sample counts of Amboseli and eastern Kajiado continuously since 1973. Details of the counting method and previous counts can be found in published papers (Mose & Western, 2015; Western & Mose, 2021) and on the ACP website.

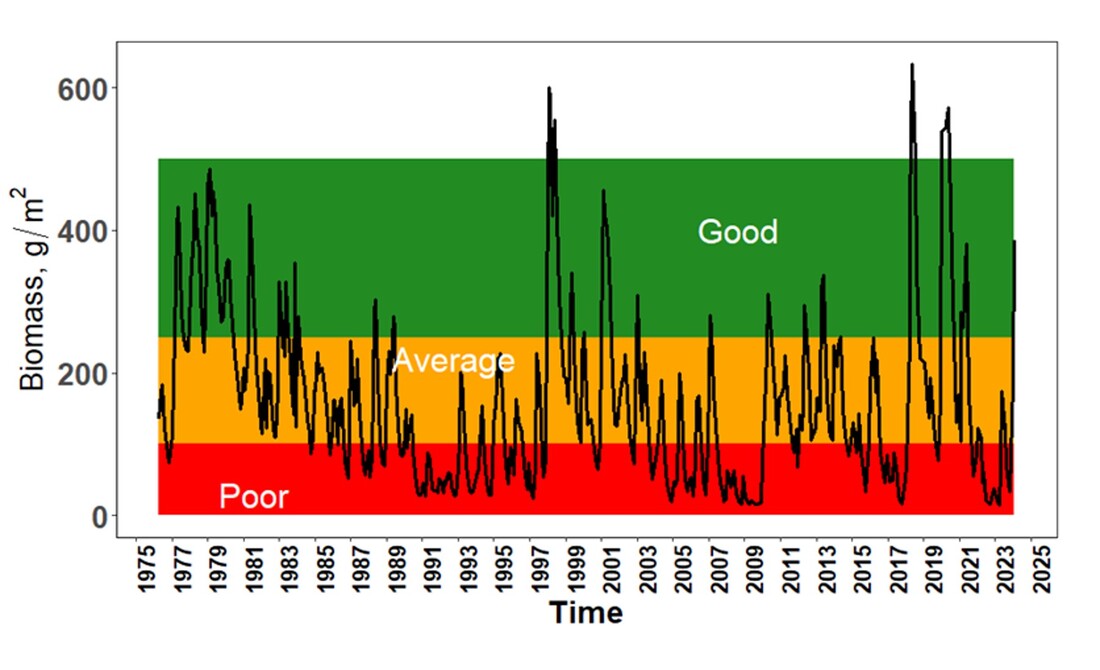

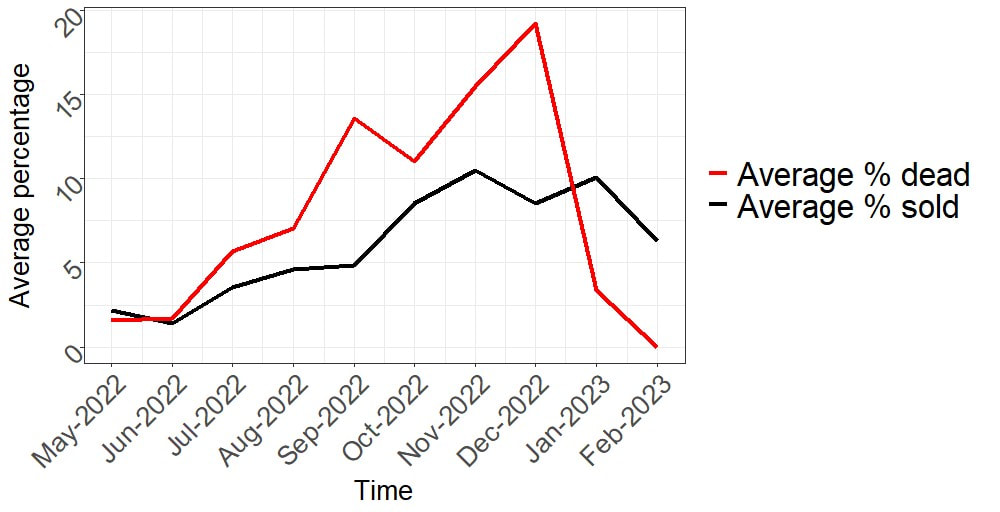

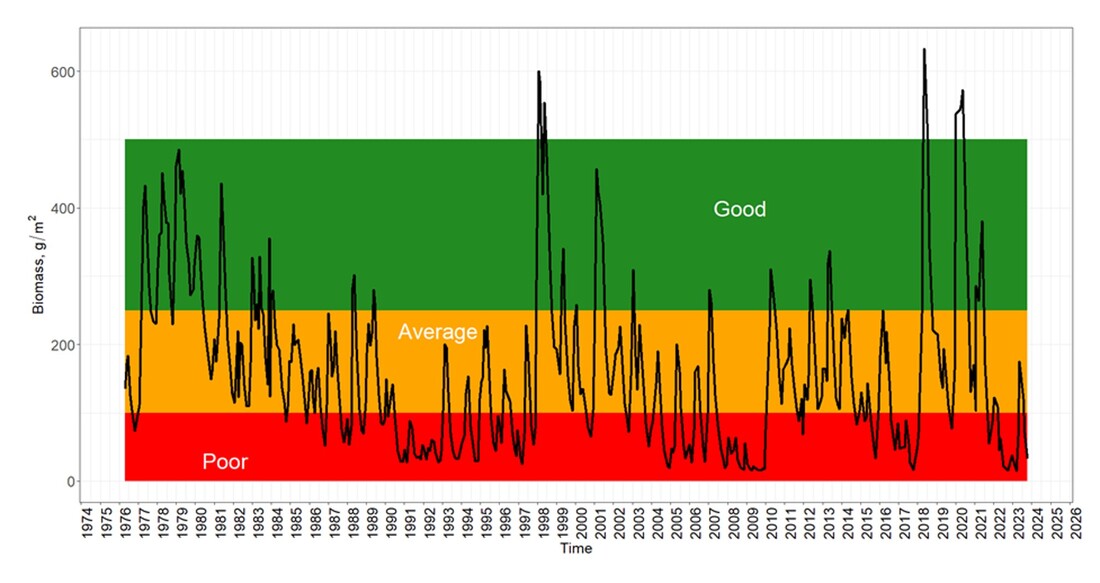

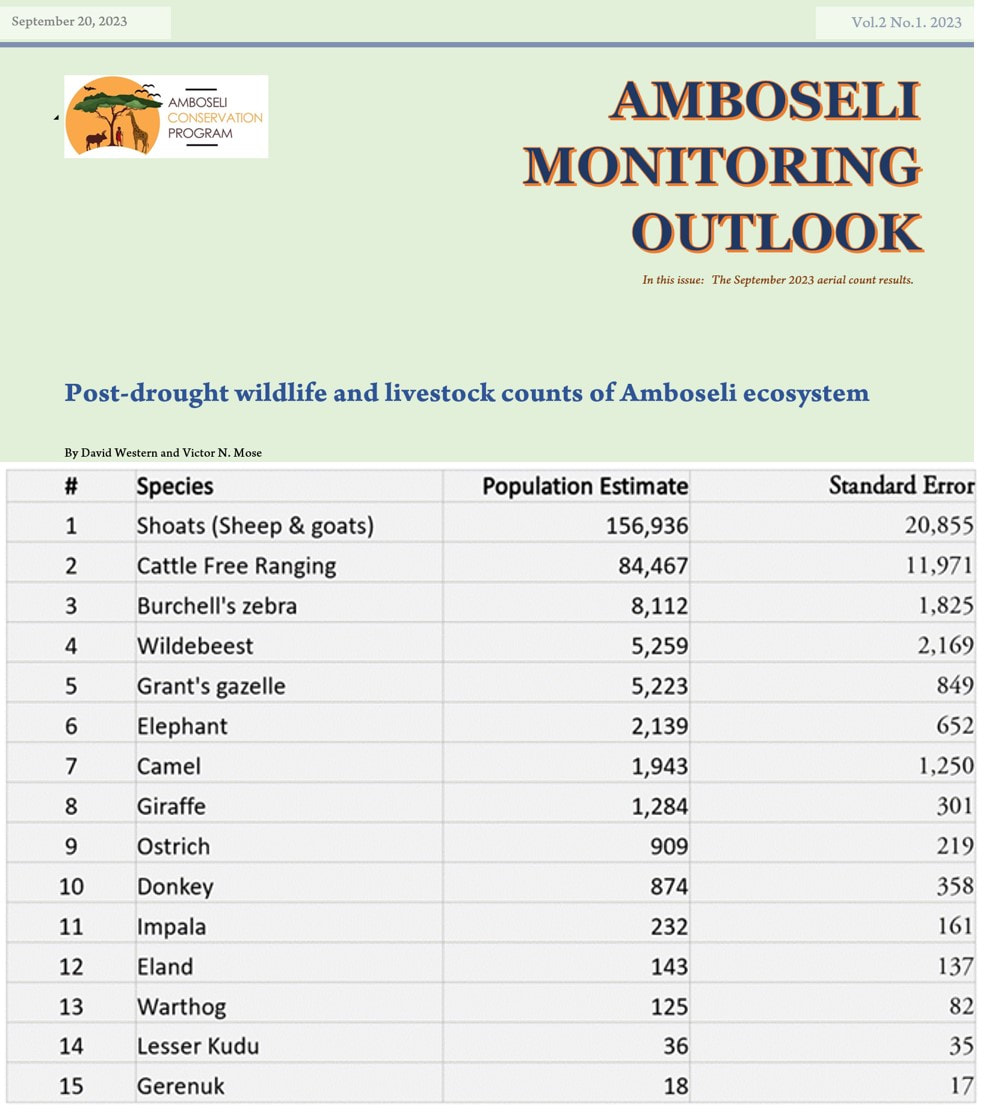

In May 2024 African Conservation Centre (ACC) and ACP, funded by the European Union-MOSAIC project and The Liz Claiborne & Art Ortenberg Foundation (LCAOF), commissioned the Department of Regional Surveys and Remote Sensing (DRSRS) and Flight Training Centre (FTC) to take stock of the recovery in wildlife and livestock in the aftermath of the 2022-2023 drought. The count was timed after the birthing seasons of wildebeest and cattle were delayed a year by the drought. The rain season count was flown across the 7,800 km² of Eastern Kajiado between May 21st and May 25th when the herds were maximally spread on migration and easily visible against the green vegetation.

| aerial_counts-may_2024_amboseli.pdf |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed